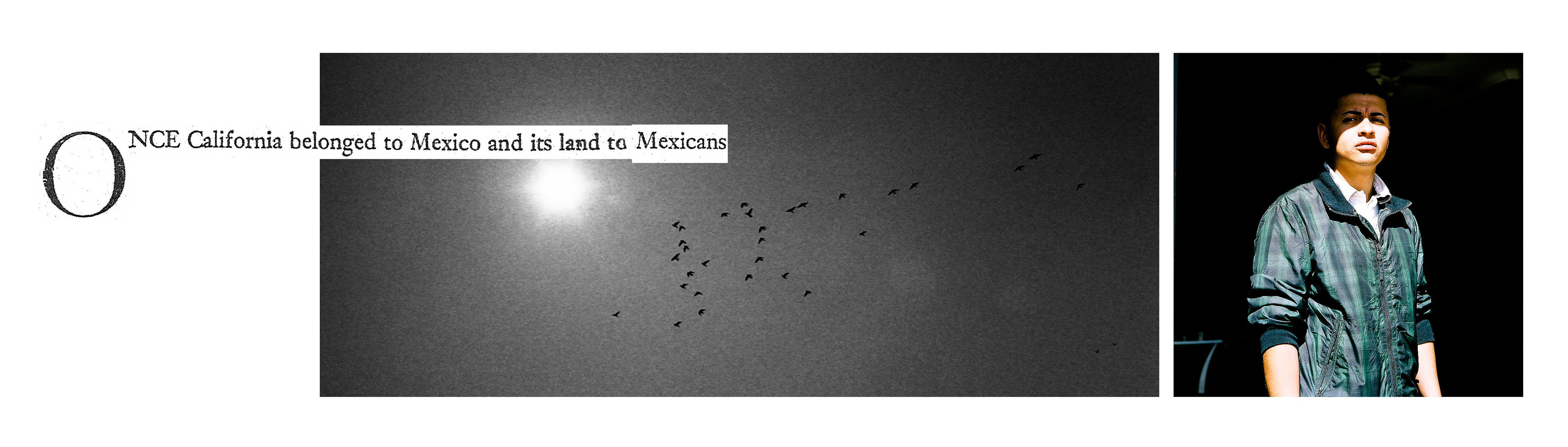

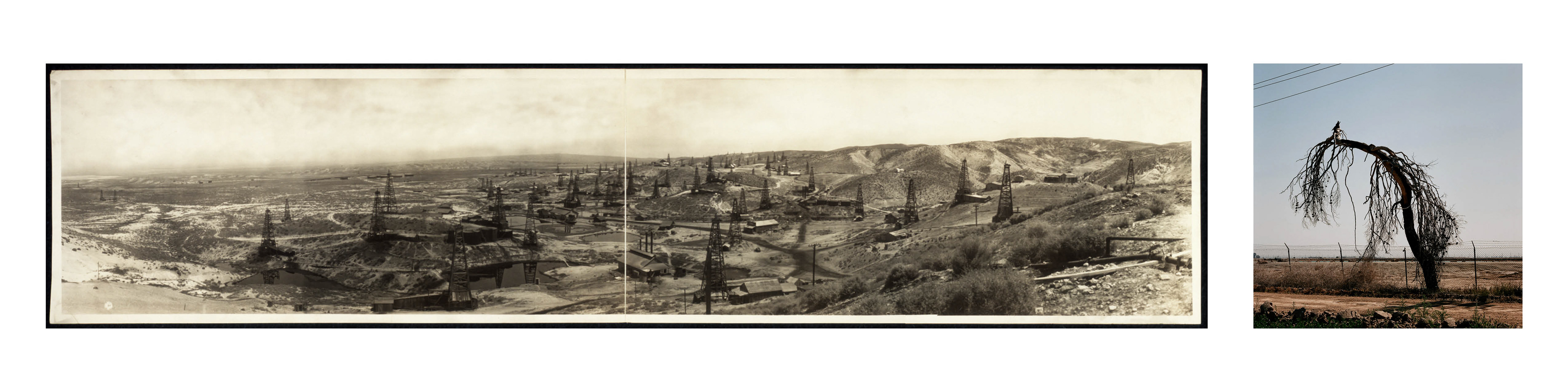

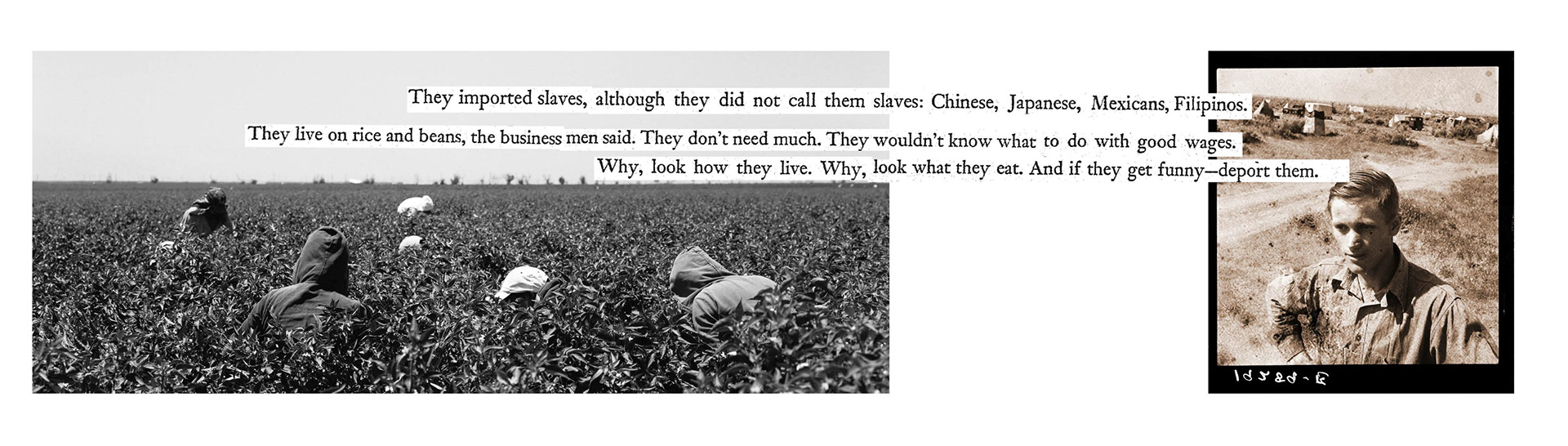

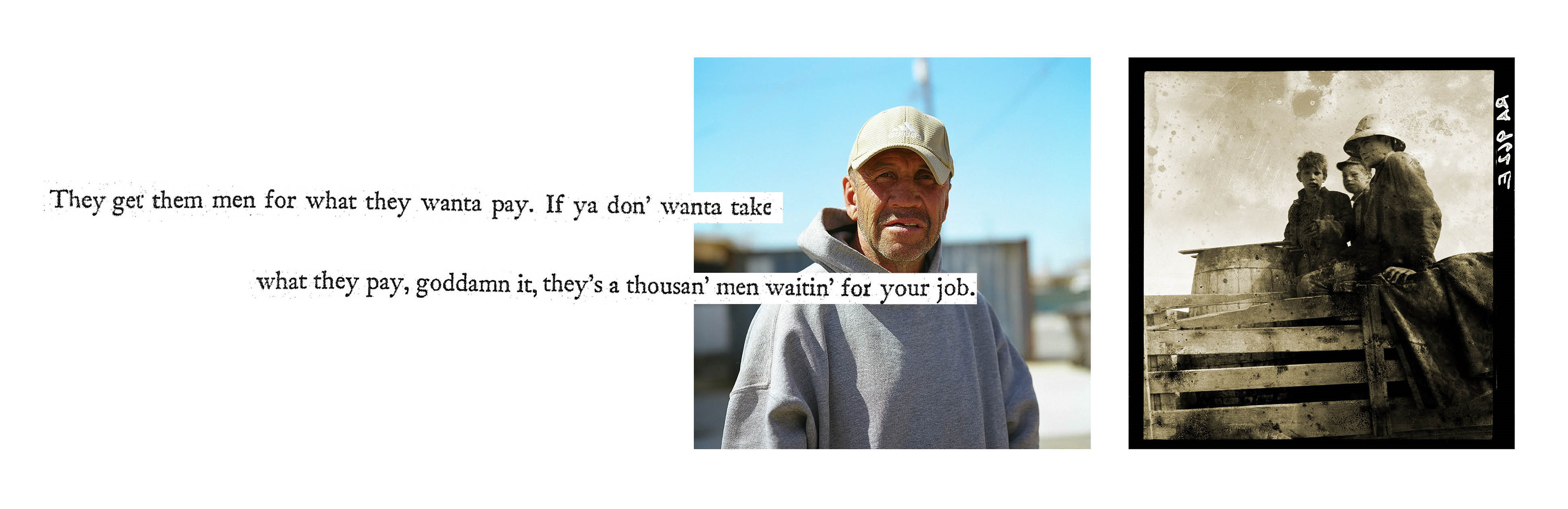

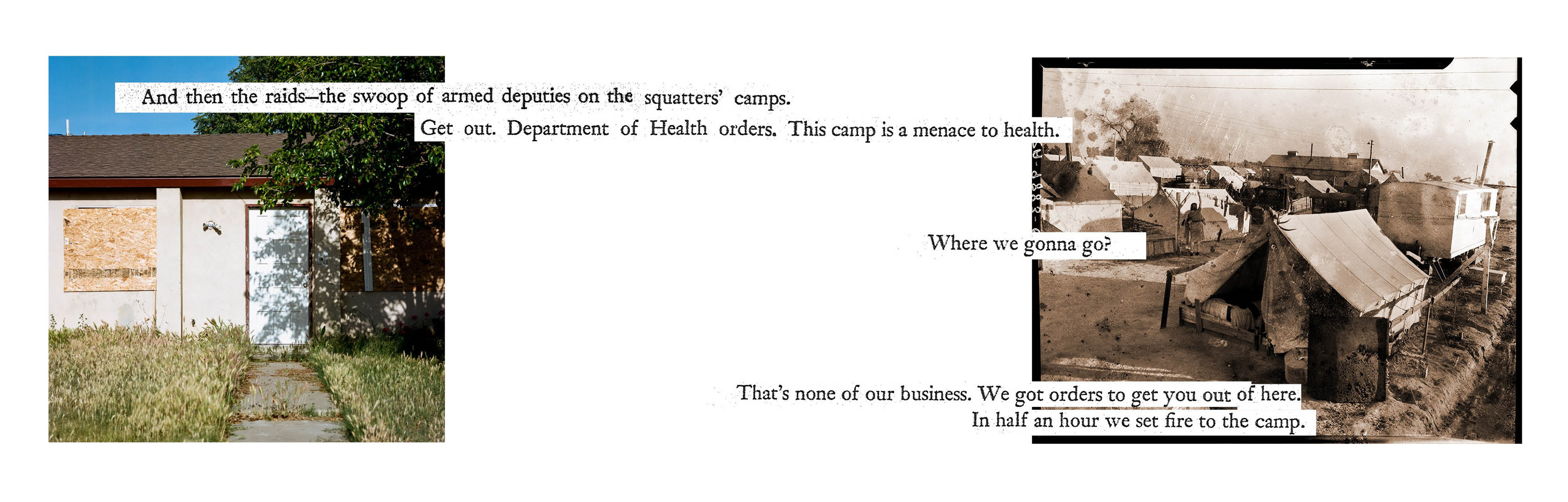

The dawn came, but no day considers legacies of dispossession, violence and displacement in California’s Central Valley stretching over nearly 100 years. Intersectional collages engage with archives and literary texts from the Great Depression and contemporary photography.

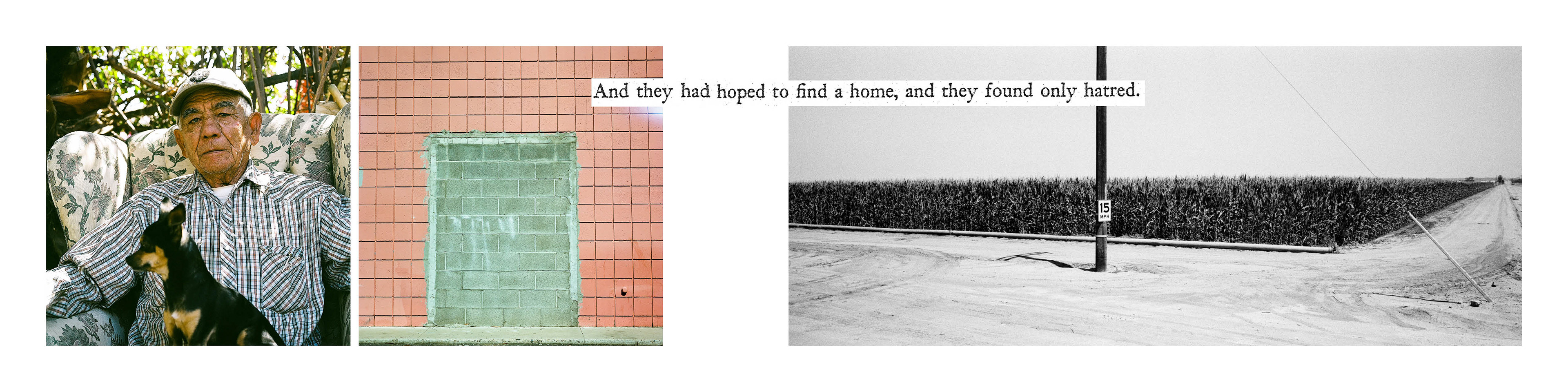

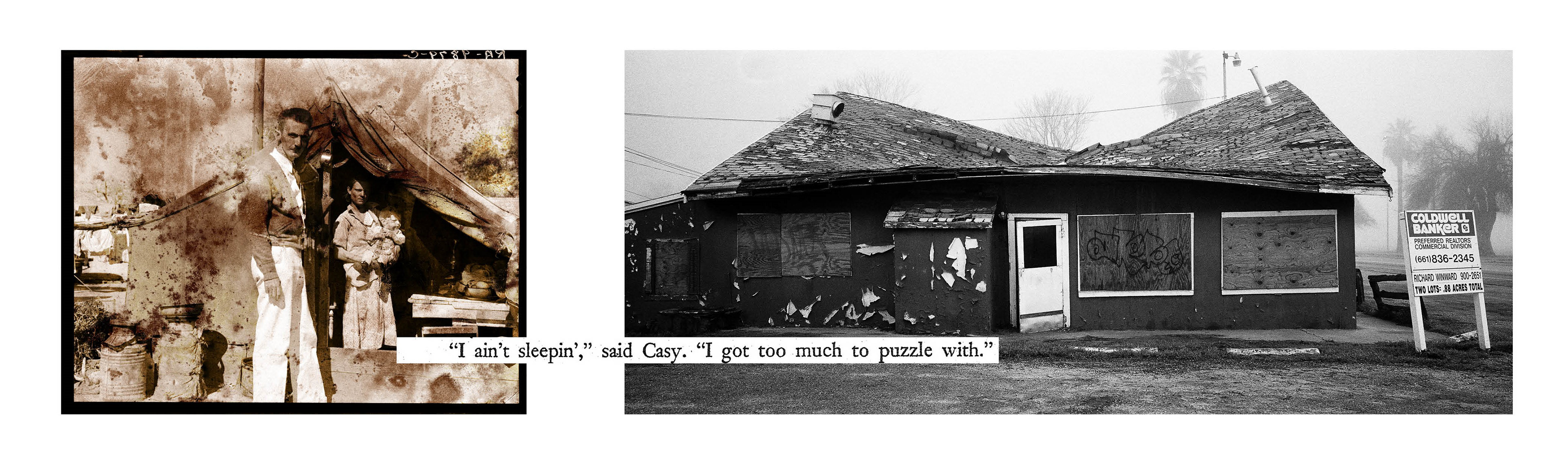

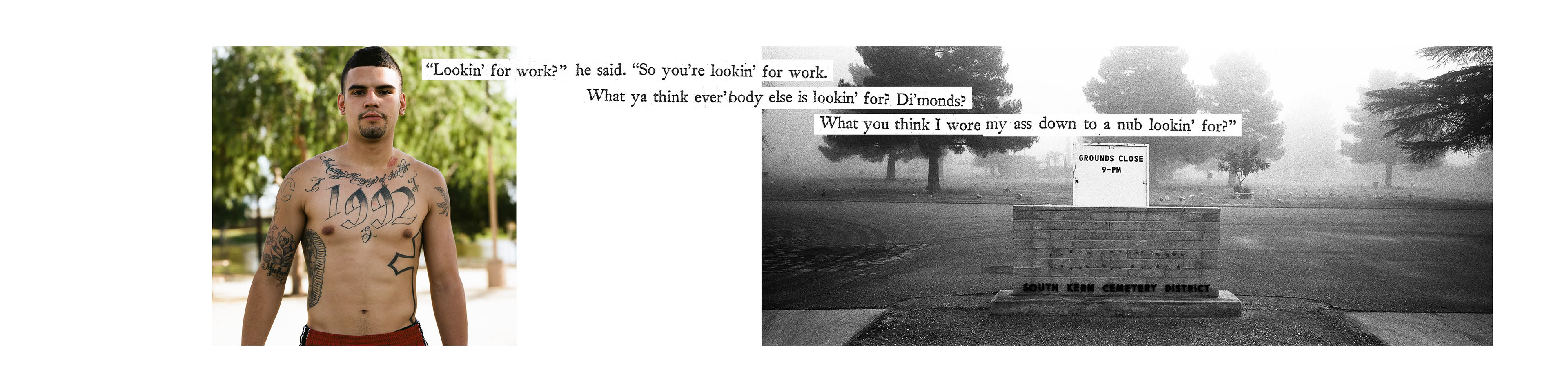

The contemporary photography is from in and around Arvin, California, near Weedpatch Camp, the famed “Okie” resettlement camp in John Steinbeck’s epic “The Grapes of Wrath.” Arvin was one of the main centers of migration during the Great Depression and it is now a community with an overwhelming majority with Mexican/Latinx/Hispanic heritage and recent migrants. This marginalized and invisible community subsists in the shadow of one of the richest and most fertile lands on earth but is shackled with high unemployment, poverty and pollution rates and extensive environmental degradation. They create the verdant land and crops but have absolutely no access to its source and riches. Their situation was not very different during the Great Depression. Legacies of and dispossession and economic violence persist over generations.

“The Grapes of Wrath” speaks to this dispossession as do the photographs of Dorothea Lange: both intertwined into these collages.

The title of the project, “The dawn came, but no day”, is lifted from the pages of “The Grapes of Wrath.”